The EU Web Act - an alternative timeline

We are at the dawn of the generative AI revolution - the most significant technological innovation since the World Wide Web, and possibly the most significant ever. AI might be our last innovation, because all future innovations will be invented by AI.

The first provisions of the new EU AI Act recently came into force. I welcome the intentions of the EU AI Act, but it creates wide-ranging compliance hurdles for EU businesses at a vital time when we need to embrace the future, or opt out of it.

Every business that uses AI in the EU will be affected. Any business that uses AI is an “AI deployer”, and at a minimum inherits a burden of proof to demonstrate that it is using AI in “low-risk” ways, should have a “voluntary code of conduct” for AI, and have trained its staff in how to use AI in a way that complies with the new regulations. The definition of “low-risk” AI is ambigous, and I understand that a proper legal analysis will likely cost more than €200k in Ireland right now. Although the average business probably won’t be in the crosshairs of regulatory enforcement any time soon, it will be exposed to civil litigation, and its suppliers will demand indemnity against the catastrophic level of enforcement that the AI Act threatens. Many businesses will avoid using AI as a result.

I’ve tried to understand the EU AI Act during the last 3 months, and I am very concerned. To illustrate this, I’ve imagined an alternate history in which the EU greeted the dawn of the web with a 1995 Web Act, transposed from the EU AI Act. I wrote this post to explore that thought experiment.

Some people who are deeply concerned about the societal risks of AI might call this a false equivalence, but let’s acknowledge that the web has also caused a myriad of damage: disrupting movies and music, closing down high street stores, killing newspapers, enabling mass digital surveillance, promoting misinformation, radicalisation, creating monopolies, breaking democracy and damaging mental health. If the comparison with regulating the 1990s web seems absurd, that’s the point. Early heavy regulation might have been warranted by the damage the web ended up causing, but in hindsight it still seems absurd because we can see how it would have left Europe in the digital dark ages.

So, let’s walk through that absurd alternative timeline and see what a 1995 EU Web Act might have looked like, with the AI Act as inspiration.

Welcome to 1995

Windows 95 has shipped, with a TCP/IP stack shoved in at the last minute. AOL and CompuServe are racing to offer web access alongside their proprietary services. Europe’s early lead with Minitel is long gone. The breakout succes of the Mosaic and Netscape browsers have met retaliation from Microsoft with Internet Explorer v1, and the browser wars are igniting. Everyone has a free “home page” on GeoCities or Tripod, mostly “under-construction” with a hit counter in the teens. Will unfettered webpage creation lead to the collapse of traditional industries? Already, some early online mail order sites (dubbed “e-commerce”) are gunning for high street bookshops, while pirate websites allow downloading of “MP2” music files, potentially damaging CD sales. Some analysts even predict that the “information superhighway” could totally revolutionize business, commerce and media.

Against this backdrop, the (fictional) 1995 European Web Act established a comprehensive framework for regulating emerging web technology. It sought to safeguard fundamental rights of online cybersurfers, while leading the world with the web’s first legal framework, providing regulatory certainty, and hoping to usher in a new age of European-led cyberspace innovation. Just like the EU AI Act that would follow it 30 years later, it would impose a tiered risk-based framework for web pages, ranging from low-risk webpages like small personal blogs, to high-risk and unacceptable webpages.

High-risk webpages included sites that might affect a citizen’s fundamental right to access to health, work, finance, education, public services etc. For example jobs boards, transport booking, online banking and educational content.

Unacceptable webpages warded off specific dystopian scenarios, such as:

- Online manuals for critical machinery and physical infrastructure, which might contain information of unproven provenance, and should not be allowed to replace trusted official paper service manuals.

- Web forums with social scoring systems, awarding some kind of reputation points for contributions and good behavior.

- Websites with advertising or product recommendation algorithms that might convince you to buy something you don’t really need.

- Search engines that allow you to search for people.

- Applicant tracking systems with automatic filters.

Affected businesses

Businesses were assured that they would only be affected if they wanted to have their own websites (“providers”), or let their staff or customers access the internet (“deployers”).

Special requirements were placed on web “technology providers”, who developed new technologies like WYSIWYG editors, hit counters, APIs and backend/frontend frameworks, requiring them to maintain detailed documentation, risk assessments, and compliance procedures.

Websites of systemic risk

Cleverly anticipating the pace of technological change, the EU Web Act also defined a special risk category for “websites of systemic risk” - websites containing a potentially limitless number of webpages, possibly as a result of run-away user-generated content.

Thanks to the EU Web Act, Europeans could rest assured that they couldn’t access unacceptable websites even if they wanted to, that innovators would all be registered in a central database, and that anyone who wanted to create a webpage would have done their compliance paperwork in advance, and (if bordering any high-risk categories) would have filed their paperwork with the Web Office in advance.

Importing Webpages into Europe

But what about web technology from outside the EU? Well, if an EU business was making tech or content from a non-EU website available in the EU then they would simply an “importer”, with responsibility to ensure their webpages were fully compliant, as well as having a declaration of conformity and an associated “CE mark” clearly displayed on all pages (so that visitors would know that this was a webpage they could trust).

What if there was no importer, and the website was directly made available in the EU by virtue of the technical marvels of the internet? Simple. Websites served from outside the EU would have to make sure they first hired a web officer within the union to act as an authorised representative, have prepared all the usual compliance paperwork, obtained a declaration of conformity and a CE mark, and have registered with the Web Office and database before going live. (Of course, they would then perform ongoing compliance monitoring and retain all associated compliance paperwork for 10 years)

Regulators were also delighted to announce the good news to a new breed of small company that was beginning to call themselves “startups”. The startups could finally stop worrying about the uncertainty of whether they were going to be regulated. To make things easier, EU member states appointed up to 9 different state bodies each to coordinate compliance and enforcement. Anyone who found that too difficult could apply to get access to new regulatory “sandboxes”, where regulators would hold their hands as they designed their webpages.

A Tale of Two Economies

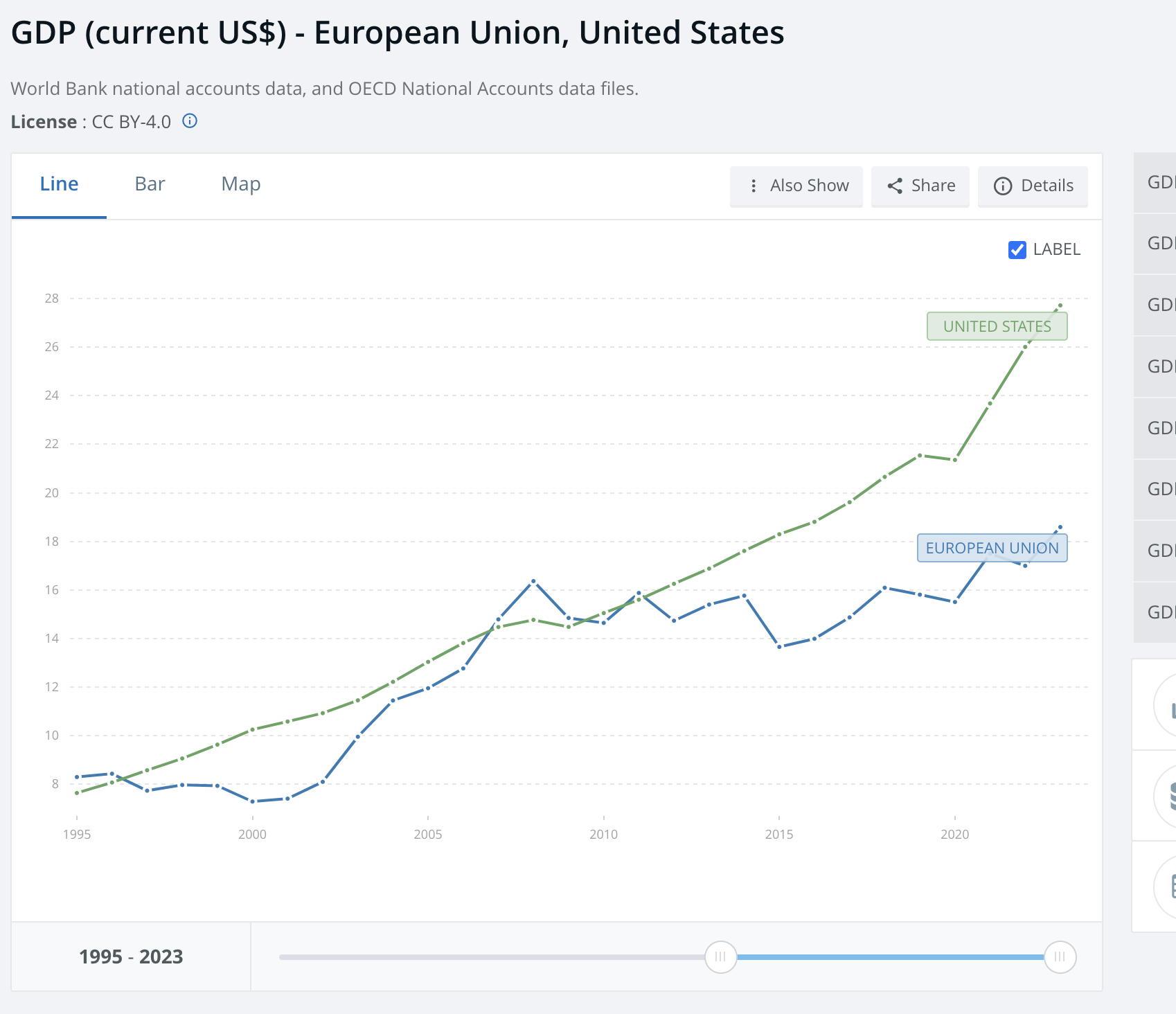

So, what would the last 30 years of the EU’s economic growth have looked like in our alternative timeline? The US and EU’s GDPs were about the same in 1995 ($7.6tn and $8.3tn respectively), but the US has grown significantly more than the EU since then (363% vs 224% growth respectively, up to 2023). The EU’s Draghi Report doesn’t sugarcoat it:

“real disposable income has grown almost twice as much in the US as in the EU since 2000”

and:

“Europe largely missed out on the digital revolution led by the internet and the productivity gains it brought: in fact, the productivity gap between the EU and the US is largely explained by the tech sector. “

Even without being stifled by the fictional regulation I imagined in this post, we (in the EU) failed to properly embrace the productivity gains available from internet and digitization over the last 30 years. We had some successful tech companies, but they never matched the wealth-creation and influence of America’s tech successes. Now, with AI poised to reshape industries just as the internet did, we are prioritising regulation over innovation.

Once again, Draghi doesn’t pull any punches:

innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations.

and

the EU should do less … showing more “self-restraint”. It will also be crucial to reduce the regulatory burden on companies.

Regulation should protect society without stifling progress, because without progress society is worse off. I also want to prevent AI-powered mass surveillance and mind control and biased blackbox AIs gatekeeping fundamental services, but I can’t celebrate this new law. I am afraid we will look back in a few years as ask why European businesses failed to keep pace in AI adoption, why Europe was outstripped by faster economies, and why Europe remains dependent on foreign imports for what little AI it uses. The answer might be the EU AI Act.

Appendix: Comparison of (fictional) EU Web Act vs. EU AI Act

(courtesy of of ChatGPT)

| Fictional EU Web Act (1995) | Real EU AI Act (2024) | |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Justification | Protect fundamental rights online, prevent disruption in traditional industries (e.g., newspapers, bookstores) | Protect fundamental rights, prevent harmful AI applications, ensure trustworthy AI |

| Risk-based Framework | Webpages categorized into low-risk, high-risk, and unacceptable risk | AI systems categorized into minimal risk, high-risk, and unacceptable risk |

| High-Risk Applications | Webpages affecting health, finance, education, and public services (e.g., online banking, job boards) | AI systems used in recruitment, healthcare, finance, education, and public services |

| Unacceptable Applications | Web-based social scoring, manipulative ads, search engines for people, automated job filtering | AI-based social scoring, manipulative behavior prediction, biometric surveillance |

| Regulation Scope | Affects businesses hosting or developing web technologies | Affects businesses developing or deploying AI models |

| Provider Responsibilities | Developers of web technologies must maintain documentation and risk assessments | AI providers must maintain technical documentation, risk assessments, and compliance procedures |

| Systemic Risk Category | Websites with limitless user-generated content (e.g., Geocities) | General-purpose AI models and foundation models with systemic impact |

| Import Regulations | Foreign webpages require an EU-based representative, compliance certification, and a CE mark | Foreign AI models must have an EU representative, regulatory compliance, and conformity assessment |

| Enforcement & Compliance | Multiple national regulators enforce compliance; regulatory sandboxes for small businesses | National regulators and the EU AI Office enforce compliance; AI sandboxes for startups |

| Impact on Innovation | Heavy compliance burden would have stifled web innovation, slowing European tech growth | AI Act could impose compliance burdens, potentially limiting innovation in Europe |