The Parallel Entrepreneur

My first shot at business was early in college, making simple websites for small companies. It was the first step on a career of company creation. Many years later I’m proud of never having had a real job, and prouder of the startups that turned into real businesses. Over the last year, I’ve begun to think about “startuping” more scientifically, with a focus on managing risk. Under the best of conditions most startups will fail due to any number of unpredictable intrinsic or external issues. This is all in the game, as they say in The Wire, but these learning experiences can take up a lot of time. Time is money, and if you’re an entrepreneur, its your own money, not someone else’s. I started DemonWare 10 years ago, I hope to repeat that success many more times. I’m establishing a strategy to help me do that. In this post, I want to talk about the risk equation facing entrepreneurs, nail down a few facts that we can steer by, and propose a new way to start companies.

Let’s define “Startup”

First of all, let’s get a clear definition. A startup is not a business in the normal sense of the word. Wikipedia defines it as a company without an operating history, but this definition doesn’t contribute much. A startup may be incorporated and be a company in the legal sense, but operationally it is still very different from a regular business. Quora has a much more useful definition, drawn from Four Steps to the Epiphany:

A startup is an organization formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model.

It’s a group of people searching for a profitable business model, whereas a regular business is a group that already has one. This distinction is liberating. It allows us to focus on how best to conduct that search, instead of being distracted by the many issues faced later in the business life cycle (the kind that MBA programmes might address). Perhaps the most important result of the distinction is the “Fail Fast” doctrine. It’s best to call off the search if there’s no business model there, and try a different idea instead. A failed business is a bad thing, but a failed startup is a good thing. Fail fast to succeed sooner, stigma not included.

The Unwitting Entrepreneur

The trouble with opportunity is that it always comes disguised as hard work. - Anonymous

It’s possible that most entrepreneurs are in this line of work because they had early successes. Perhaps 95% of people’s first attempts at business will fail. Of these brave souls, many will be discouraged and go find a real job, perhaps glad of the exciting experience, or perhaps sad about the foregone salary. Conversely, the “startupers” behind those remaining 5% of ideas get bitten by the bug, get used to being their own boss, and come to assume they have a golden touch. There is a selection bias at work here. Serial entrepreneurs are often lured in by early success. Along the way, they learn a lot about operating startups and identifying business opportunities, hopefully resulting in a lower failure rate. But yet, it is only after being bitten by the startup bug that they learn about the large inherent failure rate. Young entrepreneurs are unlikely to be factoring in the real failure rate that their personal record is about to normalize to.

Beyond personal risk to the entrepreneur, this selection bias poses big risks to the startup. Our intrepid entrepreneur believes that failure is unlikely, and may therefore be blindsided by it. Or worse, he may accept a lack of complete failure as success, and permits the startup to trundle along for years on a subsistence income.

The unwitting entrepreneur blunders into a career of unmeasured risk, armed only with self-confidence and a personal je ne sais quoi that is merely an artifact of selection bias. This hubris proceeds to compound the risk, as our entrepreneur fails to adequately scrutinize ideas before implementing them, fails to monitor for failure, or pronounce the flogged horse dead.

For my part, I believe that I am near the end of this object lesson. Having moved on from DemonWare, I’ve spent 3 years on numerous new projects, but the “next big thing” remains elusive. I am ready to get rigorous and scientific about the search for the next success.

The Subsisting Entrepreneur

There’s a lot to love about being an entrepreneur: being your own boss, lack of bureaucracy, working on things you’re passionate about, the challenge, excitement and constant learning. However, I’d like to focus for a moment on something quantifiable: the money. To compensate for the risk and unpredictability of this lifestyle you want a decent chance of significantly exceeding the income you would stand to make in industry. However, some quick work on a napkin can show that this is harder than most would acknowledge. This puts some perspective on the cost of wasting time on searches that are unlikely to be fruitful.

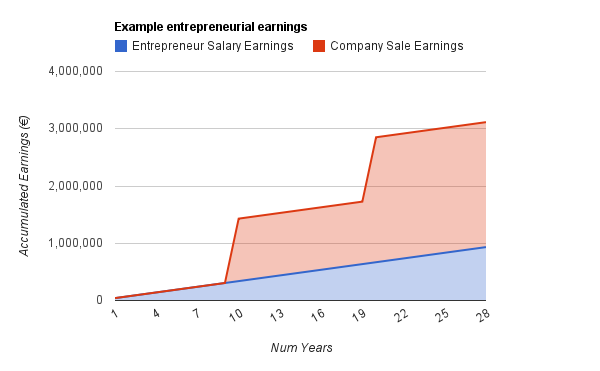

In this first chart, I made some assumptions based on the current Irish economy - the one I’m most familiar with. I assumed that the entrepreneur takes a basic subsistence salary that nets out at €33K post tax. I assumed that it takes 5 years to bring a startup to acquisition, that there’s a lock in period of 2 years, and that it takes 3 more years to find the next successful idea. This results in a startup cycle of 10 years. I assumed that given one business partner, an ESOP and dilution by investors, the entrepreneur holds 22.5% of the company at the point of acquisition. And I assumed that the average valuation at acquisition was €5 million - not a newsworthy amount, but nonetheless I think probably an average amount. As we can see, the entrepreneur’s total earnings accumulate steadily from the basic salary, and jump every 10 years or so thanks for a successful acquisition.

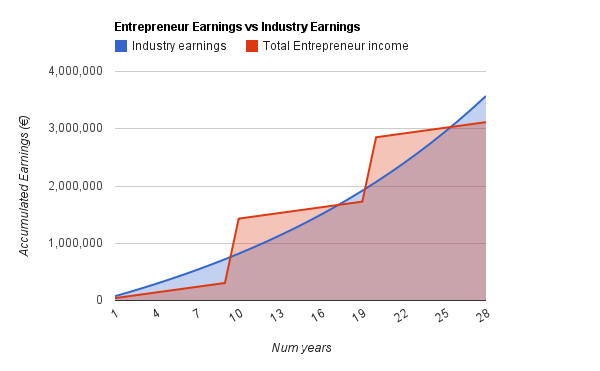

Next, I assumed that our entrepreneur can make an industry salary of about €100K gross (once again, this is very dependent on the country in question, but might be in the ballpark in Ireland for an experienced technologist). I assumed that Irish tax was being paid, and that a salary raise of about 5% was awarded each year. When we plot these together, we see that the entrepreneur who quit and went to industry is coming out slightly ahead.

I admit, that there are many assumptions in this model, but I promise you this: I didn’t fiddle with any of them to make the charts look right. This is just what came out at first blush. You might take exception to the low exit valuation of €5 million, but please remember that you only read about the high valuations in the news. Newsworthy events are implicitly out of the ordinary, and the more usual exit valuations are likely to be more… well, average.

One thing I think everyone should be able to agree on is that a simple back-of-envelope calculation like this shows us that we need to work hard to make the entrepreneurial lifestyle a good financial choice. We need to get the mean time between acquisitions down.

The Lean Entrepreneur

Anyone who follows the leading startup blogs will recognise a serious shift in how startups are being run, largely stemming from the huge reduction in operating costs offered by new technology over the last 2 decades. Nonetheless, many people are still in the old mode, often encouraged by outdated investors or advisors. Before moving on, it’s necessary to debunk these traditional expectations.

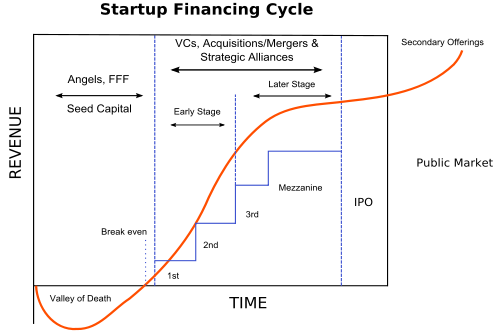

Wikipedia has helpfully provided the following graphic of the funding cycle. This kind of company starts with 6-12 months work researching and writing a business plan. Investors then successively fund the company until it reaches break-even (the “seed” phase). Bigger investors then successively hand over millions until it gets sold (or IPOs), making the investors 10 times their money back.

Whether or not this story was ever actually representative, it certainly is not anymore. Seed-level investors have realized (at least unconsciously) that times have changed, and are largely unwilling to invest in a pre-market startup. The reality is that it is now possible to get an internet idea to market on the back of personal savings. These startups are lower risk for both their founders and new investors, and their existence make the traditional ones very unattractive indeed.

The Lean Startup is the epitome of a data-driven super-fast search for a business model, enabled by advances in technology and thinking, and derived from the methodologies of Lean Manufacturing, Agile software development and the constant A/B testing now ubiquitous in the age of Google. See Wikipedia, Eric Reis, these presentations, and Four Steps to the Epiphany for more.

Here are some ways to recognise the the Lean Startup in the wild:

- Cheap. Lean startups don’t buy what can be borrowed and don’t rent fancy offices. They use open source software. They are light on senior figures and sales teams. The mission is to test business models, not actually execute them, so it avoids the expensive trappings of regular business. Premature additions weigh the Lean Startup down, increase its turning radius and hence its chance of falling apart when it needs to pivot.

- Data and measurability. The lean startup discards the hypotheses of management visionaries in favour of collecting data, experimentation, and making decisions based on fact. The one-line product description on the website will get tested as rigorously as a presidential candidate’s slogan. A culture of measurement pervades.

- Customer-centric. Anything that doesn’t serve the customer is waste. Early versions of the product will be tested by friends and family. The product will be released ASAP, with the minimum of features (the Minimum Viable Product, or MVP).

- Openly ignorant. The Lean Startup tries to know what it doesn’t know. It knows that this includes who the customer is, what the problem is, and what the best solution is. And it feels fine about it, because its mission is to find out.

In short, the Lean Startup is about quickly navigating to a good business model, largely by detecting dead ends. It is the first step to reducing mean time between acquisitions.

Unfortunately, not every startup idea can be a Lean Startup. Some perfectly good ideas may take a lot of up-front investment to build, may be intrinsically hard to measure, or may be subject to slow customer feedback.

Take a hypothetical startup that is building cutting-edge chairs and selling them to enterprise customers. This company has (1) physical production costs, (2) a physical product that isn’t online and instrumented for data collection, and (3) has sales cycles between 3-9 months, placing a hard limit on product feedback and customer centricity.

The Lean Startup is incompatible with lots of fine ideas, which must be shelved. However, you will be able to test the ones that remain quickly, at low cost.

The Parallel Entrepreneur

So far, I’ve been talking about the serial entrepreneur, who moves from one idea to the next, focusing on each as hard as possible. The problem with serial entrepreneurialism, even the Lean variety, is that it’s too slow. Even with the best the Lean movement can offer, it takes years to hit a good idea, and many more years to bring it to a saleable point. It might shave 2-3 years off the startup cycle, but it still leaves time for just a few big ideas in the average career.

I want to challenge this way of working, and introduce the parallel entrepreneur. The parallel entrepreneur mitigates risk by managing many projects at once. This portfolio may include projects at many different stages - undeveloped concepts with viral landing pages from Kickoff, through to revenue-generating operations with actual staff. The parallel entrepreneur is okay with spreading himself a bit thin if it widens the net so he can catch more potentially profitable ideas that have a ready market.

What you need is plenty of ideas. Thankfully, they are very cheap. Once you’re in flow on one startup idea, you start seeing them everywhere. In our experience so far, about 30% of our ideas fit the basic criteria that we believe make them compatible with our approach:

-

Commercializable

Some ideas just don’t lend themselves to commercialization, no matter how popular they are. For example, this could be due to a user expectation of free service, confusion over IP ownership, or straight-up legality (e.g., gambling or file sharing). -

Cheap to reach Minimum Viable Product

We expect to burn through a lot of ideas before discovering a big opportunity. They’ve got to be affordable. -

Fast to reach Minimum Viable Product

See (2). We’re planning on 2 - 4 man weeks per MVP. -

Measurable

The purpose of the MVP is to gauge customer interest and reaction. We therefore need the MVP to be capable of being easily and liberally measured. -

Consumer or “Prosumer” oriented

To measure anything, we need users. On a short timescale and budget, this means reaching lots of potential customers over the Internet, which means the product must be aimed directly at consumers, or a significant professional user market.

In most cases, these criteria translate into consumer/prosumer oriented web and phone apps.

We are implementing basic versions of all our matching ideas, building a portfolio. We will be actively marketing each idea, and monitoring KPIs to see which ones seem to be connecting with a market. We are running all of projects from our main company, but will probably spin out any that warrant a significant investment in time.

We will need to keep the portfolio well-pruned, killing any ideas that have proven to be lacking in potential. We will also need to figure out what to do if more than one idea is strongly validated and deserves a lot of time: whether to choose one to focus on, or to divide time between them? My feeling is that the risk mitigation benefits of the portfolio extend right through the startup life cycle, and that it would be great to find a way to work with two or three fully-fledged startups at any given time. This may be feasible given startups with different requirements at different stages. We can feed a pipeline of startups from the idea portfolio, with each benefiting from full-focus nurturing during its early life. Like all good startups, those that survive childhood will need to be able to operate independently when their parents are away (or cashed out).

There are clearly many details to be worked out here: when to kill an idea, when to spin it out, how to split time between developing new ideas and managing existing ideas (to mention a few). These are all interesting and tractable problems that I’m sure we’ll figure out, and that I’ll have fun blogging about.

The Problematic Entrepreneur

Unfortunately, the parallel entrepreneur has some new problems. Working on many ideas simultaneously means that none get your full attention. Meanwhile, investors will understandably want 100% commitment. Another problem is that developing each idea part-time will make it difficult to work with different collaborators. Unequal commitment to a project will likely breed mistrust among those working on it, as well as difficulty establishing what a fair ownership split would be.

I can live with having to work harder to convince investors, but losing opportunities to collaborate with others is hard to swallow. Great things come from working with great people, so I want to find a way to easily work with other entrepreneurs while maintaining a parallel approach.

In our next episode…

I believe it would be possible for a cooperative organisation of entrepreneurs to manage a collective portfolio of ideas and companies. Such a co-op would not only make it possible to work on more ideas with more people, but it could make each idea easier to investigate. An umbrella organization, owned by its members, creates opportunities to greatly improve collaboration and streamline the development of ideas. This may sounds wacky, but I’ve already found supporters. Stay tuned for my next post, The Startup Co-op.

I believe it would be possible for a cooperative organisation of entrepreneurs to manage a collective portfolio of ideas and companies. Such a co-op would not only make it possible to work on more ideas with more people, but it could make each idea easier to investigate. An umbrella organization, owned by its members, creates opportunities to greatly improve collaboration and streamline the development of ideas. This may sounds wacky, but I’ve already found supporters. Stay tuned for my next post, The Startup Co-op.

Archived Comments

October 31, 2011 at 4:52 pm, Dylan says:

This is an awesome post and every founder (or founder-to-be) should read it.

The parallel approach works to a point (I use a variation on it) but my total population of projects is usually very small (maybe 2-3 at any one time). Once a clear leader has been established I crunch on that to get it up and running (in every sense). I think it’s pretty challenging to be involved heavily in multiple fully-running startups though.

November 1, 2011 at 10:40 pm, Josh Ledgard says:

Thanks for the mention of KickoffLabs. I wrote a post about your startup co-op idea a while back pushing larger companies to create these…

http://www.startupnw.com/seattle/content/a/articles/item/492

November 4, 2011 at 7:21 pm, Simon Dobson says:

Fantastic stuff!!

Takes me back to when we did Aurium, and the things we simply couldn’t do then that’d be no-brainers now. I ran the company out of the President’s Bar in the Davenport for the first two months, but we then needed offices: now you’d be crazy to rent premises just to write code in, assuming your engineering team was used to working distributed.

November 6, 2011 at 9:59 pm, Liam Ryan says:

Interesting post Sean. I enjoyed reading it!

I like your approach here to essentially spreading yourself lean in a number of ideas (with the hope that one of them could be that special nugget of gold that will rocket you into fame along side the Zuckerbergs and Dorseys) but what happens if one, two or three of the ideas could end up being that next Facebook or Twitter?

If a parallel entrepreneur spreads himself/herself too lean, they could really miss their window of opportunity. And what if they see a real opportunity in say 2 or 3 of your lean startups, what do you do then? Bite the bullet and make a choice? What if it’s the wrong choice?

Realistically you can’t share your opportunities with a ‘co-op’ so to speak, because the founder is the only person that can truly execute a vision for the idea. But, if we can harness the vision within this ‘co-op’, together with entrepreneurs who can act together for the ‘doing’ part…then we’re onto a winner.

As much as I like the idea, I can’t help but feel that personal greed could be the down fall of this co-op without proper structure and rules (comfortably adhered to by each member) in place.

Interested in hearing more though!

February 29, 2012 at 9:35 am, Mark Hegarty says:

This is a superb post. Coming to it a little late though. I want to link this to our blog if I may, as a post.

I like the quote “”The trouble with opportunity is that it always comes disguised as hard work.” – Anonymous, its so true.

We get to speak to a lot of business start ups, and If I am ever asked for some advice when starting a business, I’m going to send people to this link. We provide small blog posts through our site. Tips and tricks to get you started with a new business if you will at http://www.irishformations.ie . Its interesting that you mention managing risk early in the post. We wrote an article on this recently: http://www.irishformations.ie/blog/starting-a-business-in-ireland-and-how-to-manage-risk/ Sean, If theres anything we can do for you, give us a call. Looking forward to following this blog.